In Nature Capturing Details

Have you maybe also experienced a sublime sight on one of your trips – and were then disappointed when it didn’t come out in the photos you took?

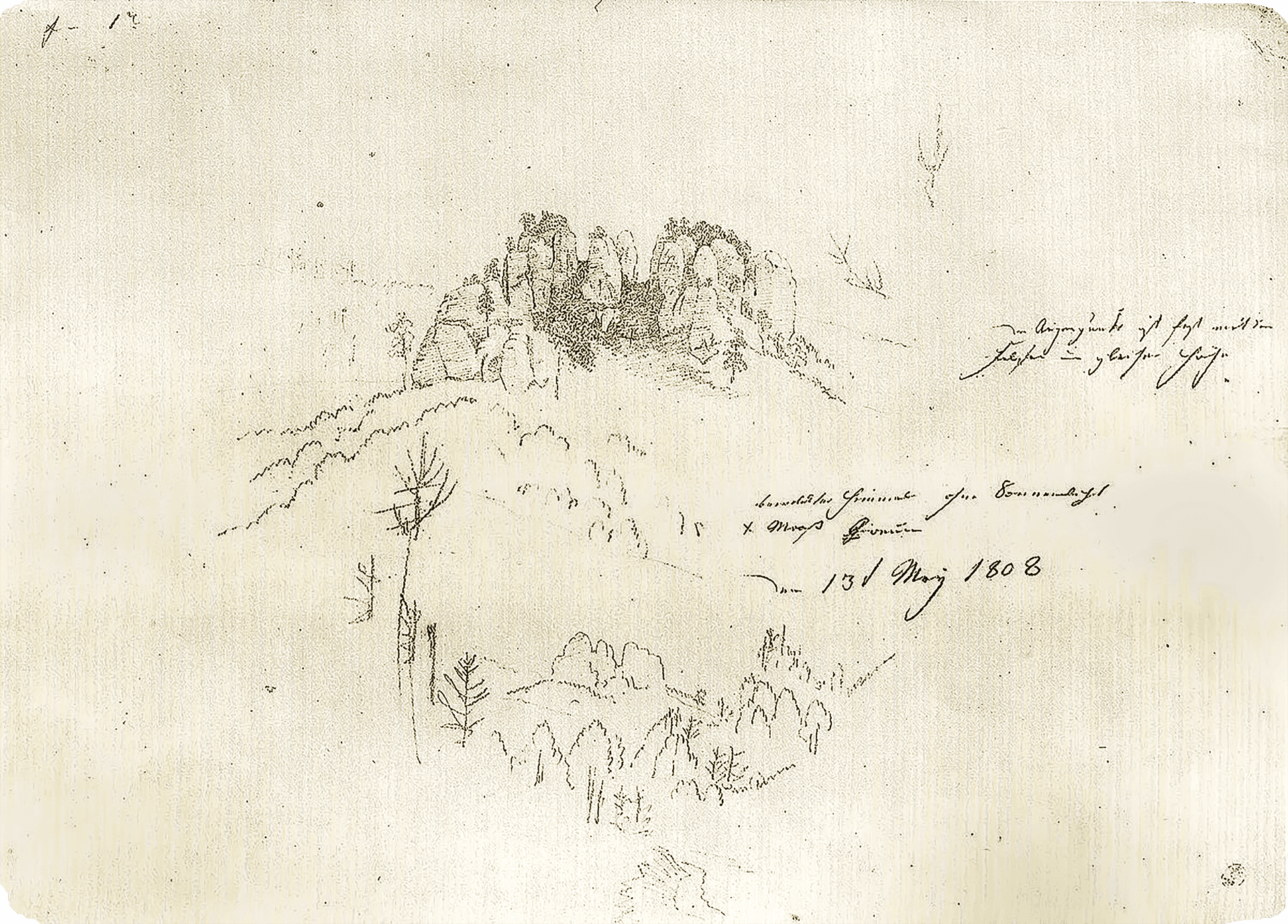

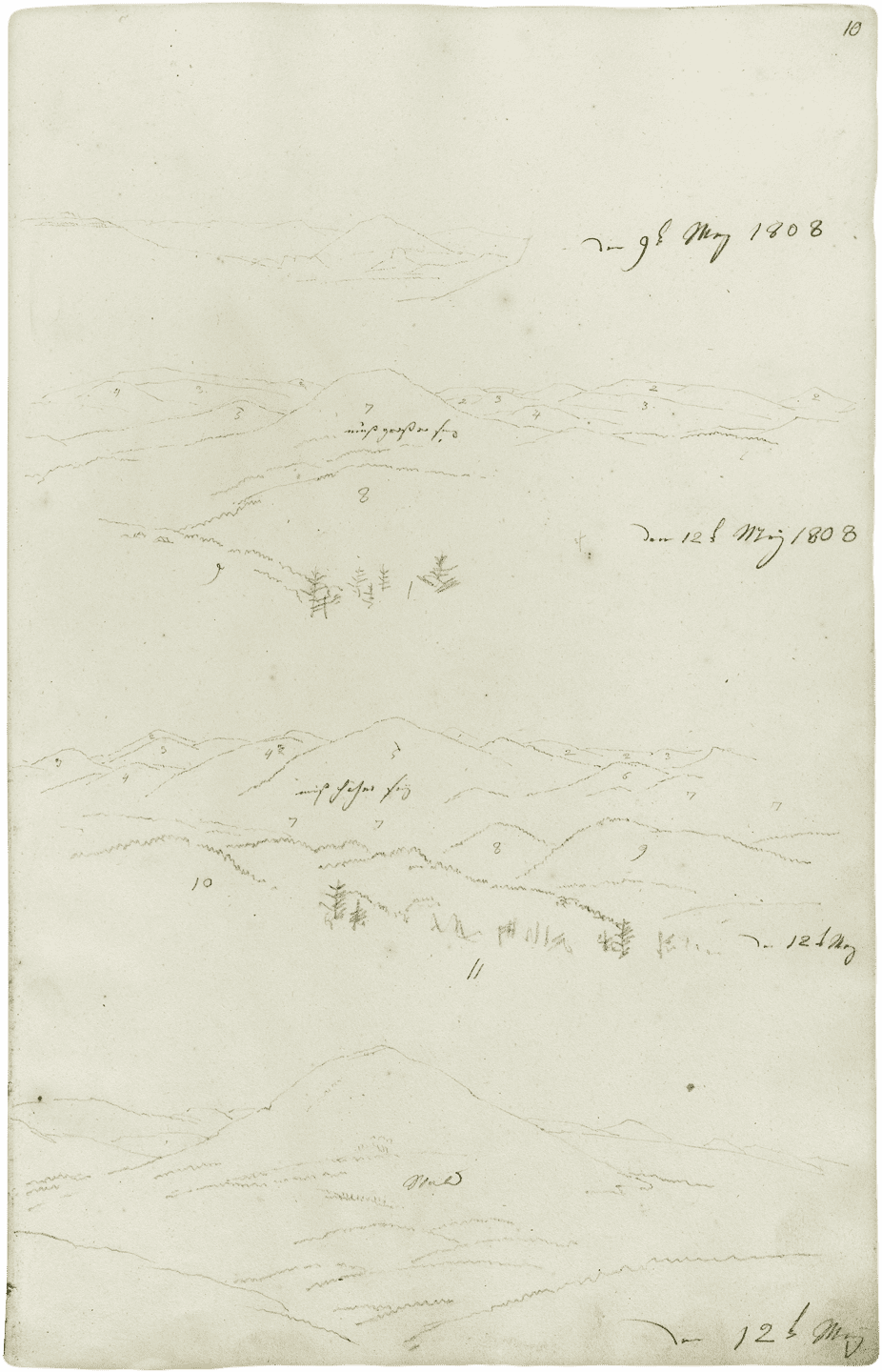

To get around this problem, Friedrich preferred to concentrate on the details. He didn’t even try to artistically capture the big picture, the sublime. Photography didn’t exist, so instead he drew. When he found a subject that interested him, he would sit down – perhaps on a tree stump. He observed closely, drew meticulously, exploring shrubs, rocks, and mountain ranges with fine lines.

Juxtaposition of detail from the painting and the drawing.

Caspar David Friedrich, Rocky Hilltop, June 3, 1813, Drawing, 11,1 x 18,6 cm, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

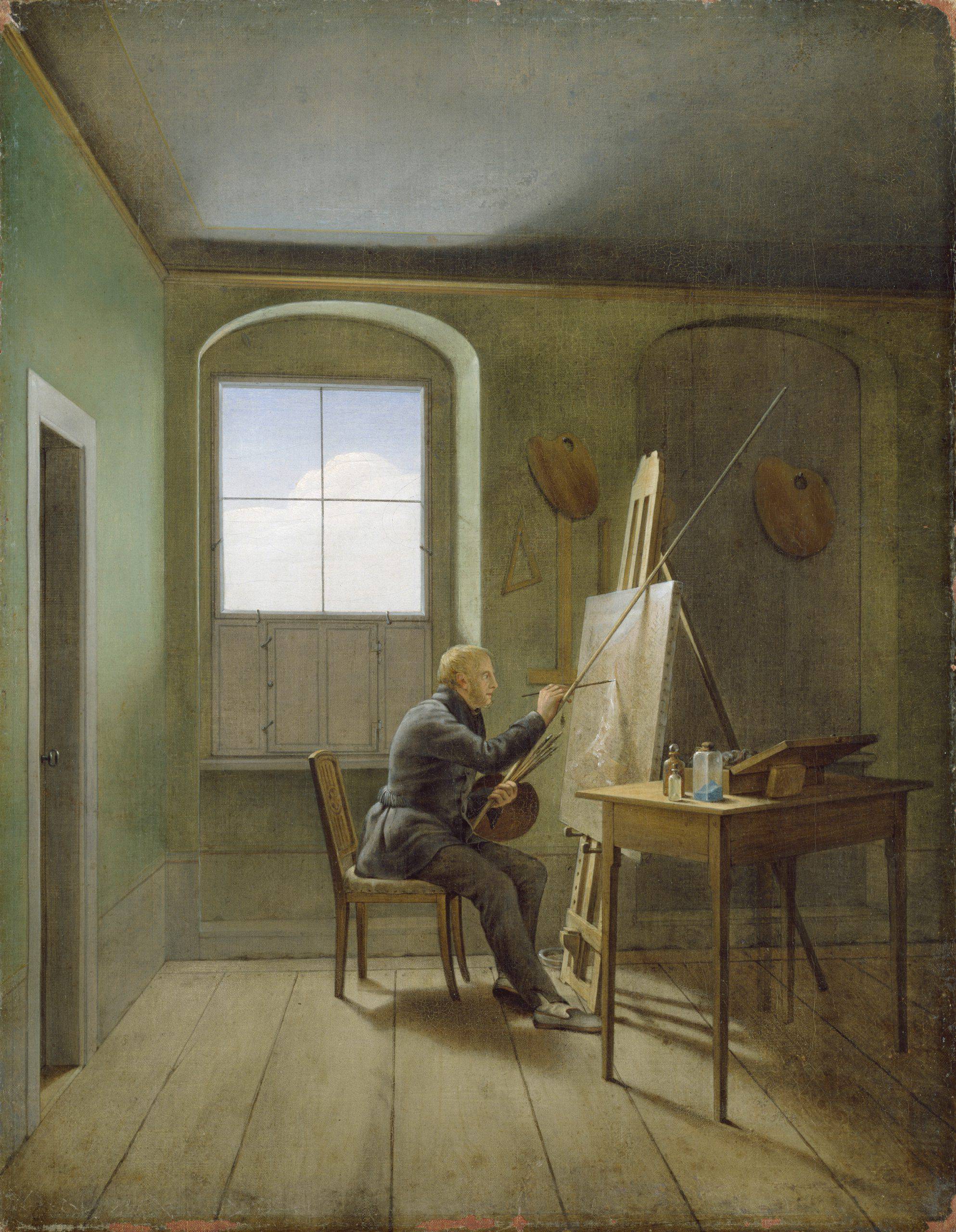

Later, in his studio, Friedrich assembled these individual nature studies into a new composition. He described his working process as follows:

Close your physical eye, so that you may see your picture

first with the spiritual eye.

Then bring what you saw in the dark into the light,

so that it may have an effect on others, shining inwards from outside.

Only when Friedrich had his picture exactly in mind, did he begin to paint. He often assembled different drawings from his travels and created something altogether new – a kind of Photoshop in his head.

Hidden in the Wanderer are many of the nature drawings Friedrich made in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains. Today, art historians can still determine quite precisely where he made certain drawings.

Because the individual elements of the landscape are reassembled, or composed, it is also called a composite landscape.

But taken as a whole, however, this landscape doesn’t exist in reality.

Caspar David Friedrich, detail from the painting “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog”

Caspar David Friedrich, detail from the painting “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog”

Maybe this is precisely what is so fascinating about Friedrich’s works today: the relationship between his observations, his ideas, and what he ultimately creates from them as a picture. A new image, composed of many smaller ones pieced together – this is something we know from today’s visual culture (just think of AI-generated imagery and deepfakes) …